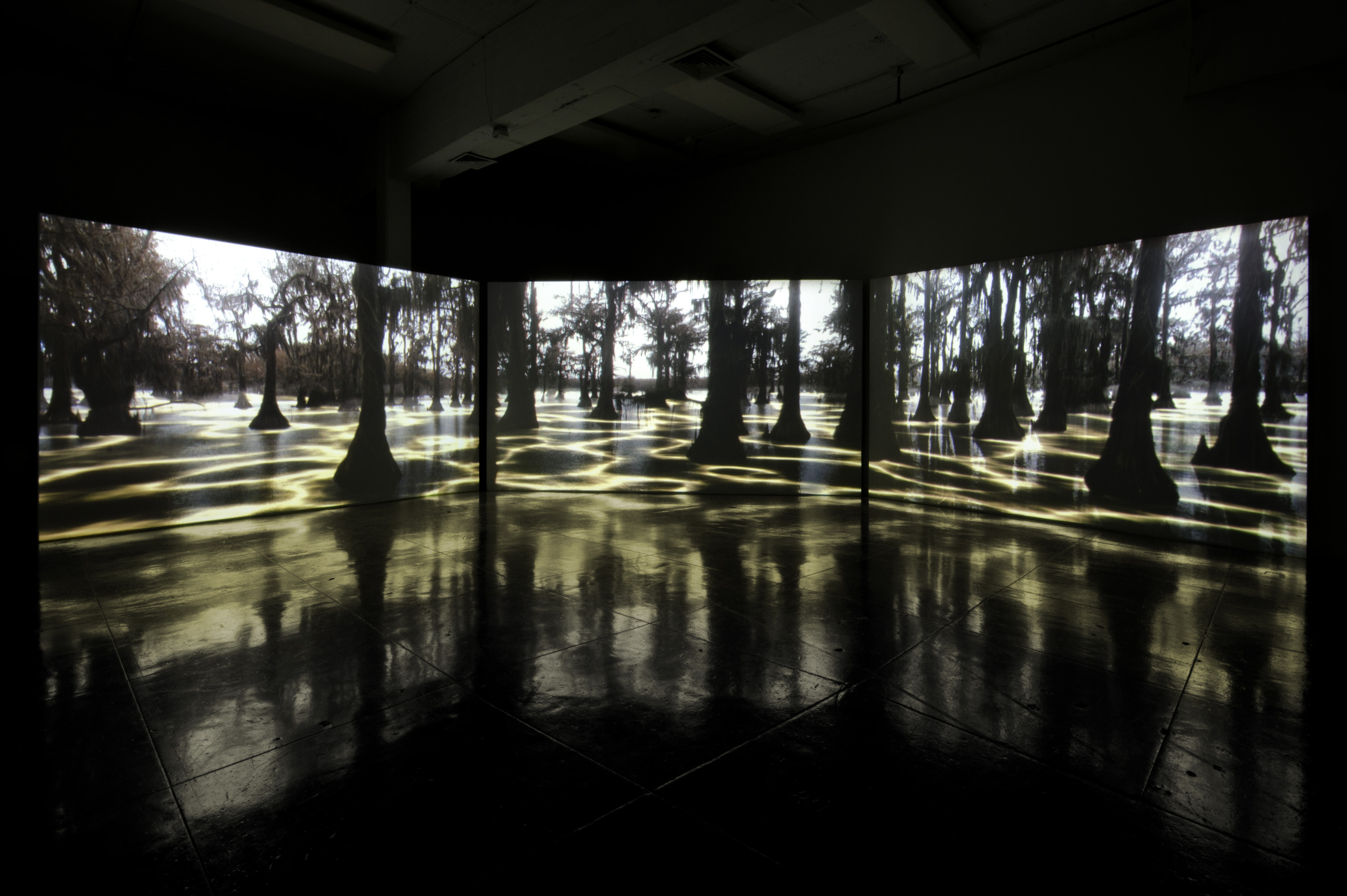

The work draws on Richardson’s distinct art practice which focusses on ideas around conservation and a careful observation of the effects of humanity on the planet. She films the bald cypress trees, indigenous to Caddo Lake in Uncertain, Texas, and manipulates the footage, creating a series of twisting, snake-like tendrils of yellowish light in the water with an eerie soundtrack replacing the sounds of nature.

Richardson explains, ‘I’m trying to create contemplative places which are both beautiful and mesmeric, but at the same time, unsettling.’

Presented as a triptych, the landscape is viewed from a single vantage point, like a painting set in motion. The immersive environment of Leviathan is entirely devoid of people and invites viewers to ‘insert themselves into the work’ and become its sole protagonists. Richardson’s manipulation of the video suggests several foreboding plot lines: the birth of primordial life, the emergence of a malign aquatic creature or a post-apocalyptic Earth.

Caddo Lake, the setting of Richardson’s Leviathan is thought to be the first site in the world for underwater oil drilling and plays a significant role in the shaping of current fossil-fuel debates concerning the global climate crisis. Tunbridge Wells has strong links to conservation, having enshrined the protection of wild plants, animals, and natural habitats in The Tunbridge Wells Improvement Act of 1889. This ground-breaking legislation ensured the protection and stewardship of the extensive commons found locally and the plants and wildlife that dwell and flourish on it.

The staging of Leviathan at The Amelia Scott comes at a significant time historically, in reflection of growing global climate concerns and places Tunbridge Wells once again at the centre of environmental and conservation debates.